Translated by Bethszabee Garner

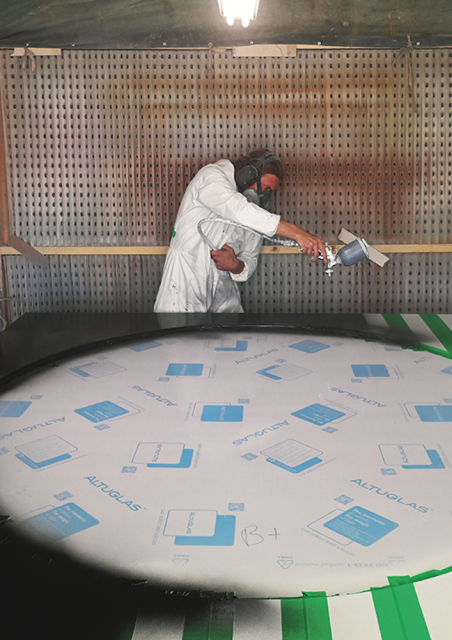

All made on site by a craftsman-carpenter, these sculptures resonate with the island, which can be explored entirely on foot. An open-air exhibition that the world-famous artist known for his vertical stripes imagined as a playground for summer visitors. An encounter in 2022 with one of the greatest contemporary thinkers of space.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: From June 28, 2022, the public will be able to visit the temporary installation on the Île d'Arz.

Daniel Buren: Yes, but you shouldn't use the word installation because I find it completely incompatible with my work. That word means just about anything: it could mean putting shoes in a shop window... No, an installation is not what I do. For almost 55 years, I have been using the term “work in situ,” which I believe I introduced into the artistic domain and which is now widely used by many people.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: A term whose definition is, and I quote: “The work is born from the space in which it is created.”

D.B.: I don't own it, but my definition of in situ covers a whole range of things: the place, the space, the time, the specific people I'm going to work with, who are always different. All of this is inseparable.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: That's to say, the random appropriation of your work by the place, by the visitors, by the context...

D.B.: It's only visible to people who make the effort to go and see it. The work itself and the term in situ are first and foremost about time, space, and people; and in space, it's obviously everything that exists in the space of the place, even if it's very small. So often, we think it's the architecture, but architecture is only one part of the whole.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: What difference do you make between a temporary exhibition in a museum, for example, and the one in Arz?

D.B.: Fundamentally, there is no difference. I do work that plays with the framework I am given. That doesn't stop me from doing what I want where I want without asking anyone's opinion... which is something I always do, even if it's much rarer than when I started out. I often respond to invitations: from museums or to work in geographical locations such as Arz, which is a field of work for me.

Desirée de Lamarzelle: And the difference between the ephemeral and the permanent?

D.B.: None. Everything could be permanent if ephemeral works were purchased, but instead they are destroyed. It is their purchase that seals their permanence.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: Were Buren's columns titled Les Deux Plateaux always intended to be permanent?

D.B.: Ah yes, because they are a public commission in a public space, so they are ad vitam æternam, unless there is a clause specifying, for example, that they may be moved or destroyed. The permanence of the work is assumed by default.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: Now a global cultural icon, they provoked extremely violent reactions in 1986…

D.B.: Yes, that was unexpected for me, and quite difficult. I had won this project in a competition and it was my first official work. At first, although I thought it was normal that the project would not be unanimously accepted, I felt protected by the fact that it was a government commission. But then it was exploited politically in the middle of the legislative campaign, with the right accusing the left of damaging the public space as a listed historical site... It became very complicated when the National Front threatened to destroy the site. It was all the more shocking at the time because we hadn't seen such a wave of violence—with hints of anti-Semitism—since the war. I finally surrounded myself with competent people to defend me and we were able to finish the work almost peacefully. The day after it was opened to the public, the controversy disappeared. Today, it is one of the most visited monuments in Paris, whereas the Palais-Royal used to be completely deserted.

Desirée de Lamarzelle: Have there been other works since then that have been subjected to such an outburst of violence?

D.B.: Perhaps not to the same extent, but a few years ago I was struck by what happened to the American artist McCarthy and his ephemeral “plug”—admittedly rather irreverent—which was exhibited in the Place Vendôme during the FIAC. Not only was he attacked, but his creation, which was an inflatable work, was destroyed by individuals. This is completely unacceptable behavior. I feel and fear that this is symptomatic of a current rise in intolerance and a certain intellectual poverty.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: Certain scandals have marked the history of art and shaped its evolution... Is this the case with Buren's columns?

D.B.: Yes, the scandal surrounding the columns is comparable to the artistic scandals of the mid-19th century, such as that of Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, which caused a stir and marked a certain evolution in art, with the old and the new opposing each other. These scandals were public at a time when salons were visited by crowds from all over France. While their impact could extend to the borders of Europe, I feel that today's artistic scandals are more limited in terms of time and scope.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: You talk about the “zero degree of art” as the renunciation of gesture in favor of an anonymous framework, which is what your black and white strips are. How would you define your work

D.B.: First of all, by rejecting the definition of my work as art. I have never used that word: for me, it is work—the only word I use—which has certain specificities and perhaps raises questions or issues. If people think it's art, that's their definition; it's our society, or even the society of the future, that will decide. An artist who defends himself by invoking art in what he does really makes me smile. It's not up to him to decide.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: So art is a sham?

D.B.: Art doesn't mean anything. What is it? Who is it? What does it represent? No one knows. It's a question mark over the very adventure of this process in relation to others. When you work and do something that hasn't yet been defined by others, it seems really pretentious to me to claim that it's art. Besides, those who consider what they do to be art have nothing left to do, since they already know what it is...

Désirée de Lamarzelle: There is no real definition?

D.B.: A definition could be a list of everything that has been considered art, going back thousands of years: we still don't know whether cave paintings are art or something else. In that case, we could say that Giotto and others up to Pollock are people who have done something, not only in painting, but also in relation to a great history that we call Art.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: What drives you in your work?

D.B.: Trying to find something, which obviously has more to do with drawing than making sausage (laughs). But when we say that, we obviously haven't said much. I work in space, in a way that is closer to a sculptural phenomenon than a pictorial phenomenon because I use objects. The place becomes inseparable from what I put in place, and then the eye sees differently.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: Can we describe your as a thinker of space?

D.B.: Yes, I don't know. In any case, it's certain that this work in space is undoubtedly more of a field of research today than it was fifty years ago. And I imagine that I wouldn't be invited as much if it hadn't become as important as painting and sculpture.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: You are represented by Kamel Mennour. What makes a good gallery owner?

D.B.: Someone who puts together a team of artists, preferably a coherent one, and then devotes themselves to them and defends them. And who manages to monetize the work in question. That's essential: a gallery owner who doesn't sell anything isn't a gallery owner, it's like a painter who never paints a picture.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: Which artistic periods have influenced you?

D.B.: Everything has influenced me. And it's interesting to observe that certain artistic trends don't stand the test of time, which tends to smooth out differences. Does this period still exist? Does it resist the catalog effect of art, with people who can't help making connections between works? For example, if you put Duchamp's urinal next to a sculpture by Giacometti, it's because it's no longer understood in its concept; you shouldn't be able to see them at the same time. You shouldn't be able to think about them in a coherent way, as if there were a connection. If you put it in a museum, as is the case today, surrounded by other works, it no longer works in my opinion.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: Where could it be exhibited?

D.B.: I don't have a solution, I'm not saying where the urinal should be displayed, except perhaps in a urinal, because Duchamp wanted to show that anything absolutely banal and even trivial could have a certain value. You're always betrayed by the people who put you forward!

Désirée de Lamarzelle: Could you have a museum named after you?

D.B.: Not while I'm alive! I'll do everything I can to avoid it if it ever happens.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: Do you think you have been hard on yourself?

D.B.: I think so, yes. I don't know if I was right, but when I was young, I had to get rid of some of the things I had created, let's call them objects or paintings, with the intuition that they weren't good, even when they seemed successful. As I started creating at a very young age, this gave me time to evolve and undergo a kind of catharsis to get rid of the superfluous.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: You have to know to be violent to yourself.

D.B.: Yes, people who work in a field like art—I don't dare say artists—mustn't give in to the easy way out. Sometimes it's a trap to have too much talent. Take Cézanne, for example, whose first paintings at the age of 20 were frankly awful, while others of the same age showed immense talent: you can sense that it wasn't easy for him! I am convinced that this lack of ease made him the artist who created such astonishing works. He had to completely surpass himself and create something that matched his intelligence to make up for this lack of ease. You have to constantly question yourself. Take Monet, for example, he never stopped deconstructing everything he had done, everything he knew how to do, his whole life, right up to his last works, the Water Lilies, which were absolutely innovative, bordering on abstraction.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: Your next exhibition will be in Arz. What does this island mean to you?

D.B.: It's a small island. I didn't know about it before I visited it. It's interesting because it's very flat, calm, with beautiful, relaxing landscapes. But above all, it has the distinctive feature of being surrounded by land, as there are no high points and sometimes you don't know if the land you can see on the horizon still belongs to the island, even though you are right in the middle of the water. Being able to visit it entirely on foot offered the possibility of showing the island through my works and, at the same time, of seeing them all even though they are scattered.

Désirée de Lamarzelle: It's a lovely playground…

D.B.: Everywhere I work becomes a playground, whether it's on an island or in a museum. In this case, it will also be a playground for visitors, who will be offered a walk with maps to help them find their way around, which is quite fun. I really like this idea of movement because I've always thought that you can't see what I do if you don't move. And at the same time, you visit something else that has nothing to do with my work, which is the island itself and its perspectives.

Article written by Désirée de Lamarzelle, to be found in issue n°1 of OniriQ Magazine.